Short selling: questions and confusion

Making a profit by selling a depreciating asset is an idea that’s foreign to us, and one that invites confusion. We’re conditioned to expect profit only when our assets increase in value. The house that you buy, the company that you acquire, and the business you set up are a testament to that. This is one of the main reasons short selling is difficult to understand.

The notion of selling something you don’t own is another pitfall on the road to understanding short selling. Dig deeper, and the pitfalls multiply. Inside them are foreign terms such as “borrowing fees,” “short squeezes,” “trading on margin,” “trading against the tide,” and “hedging.” Dig too deep, and you’ll find the terms have shifted from confusing to hostile. “Bear raiding” and “vulturing” begin to creep into the terminology, and you are left wondering how a two-word phrase can leave such a significant imprint on the investors’ psyche.

Upon further examination, you will find that short selling is not as complicated (or evil) as it seems. The concept is broken down once you come to grasp two core concepts: borrowing & bargaining. Clarity finally creeps in when the technical terms - margin interest, borrowing fees, hedging - are all defined and explained.

“The average trader is naturally a chronic bull. It is human nature to prefer optimism to pessimism” - Phillip Carret

What is short selling?

Suppose your friend John has a Model 1 IKEA chair he’s not using. You are in need of money, and you have an idea on how to make some, so you ask him to borrow his chair. He agrees, and you reach out to your friends, Moe and Adam. You know Moe is looking for a Model 1 IKEA chair, so you sell it to him for $300. You know Adam has a Model 1 IKEA chair that he doesn’t want, so you buy it from him for $200. When you give John back the Model 1 IKEA chair, you will have made $100, and John will have gotten his chair back.

This is short selling. The short seller borrows shares of a stock he doesn’t own from his broker and, by selling it high and buying it low, hopes to make some money before returning the stock back to its rightful owner. The difference in price when selling and buying multiplied by the share size will equate to the total profit or loss.

For example, say you short 1000 shares of stock “XXX” at $2.0 and buy back the thousand shares at $1.5. You make $500 (1000 x 0.5). If this happens in reverse - if you short 1,000 shares of stock “XXX” at $1.5 and cover it at $2.0 - you will have a net loss of $500 on the trade. When you’re shorting, you only profit when the price goes down.

It’s the same case with the IKEA chair. If you had sold it for $200 and bought it back for $300, you would have lost $100. This is one risk of short selling. If you cannot find a buyer willing to purchase back the chair at a lower price than you originally sold it, you will take on the loss.

But the bigger risk here is actually for your friend John. Suppose you don’t find someone willing to buy the chair back for less than you sold it, and you decide not to buy the chair back at all.

John will have lost his chair due to his blind trust in you.

Shorting collateral: intro to margin

Brokers and investors do not engage in blind trust. While they may lend you assets like your friend John did, they have stringent rules, conditions, and failsafes to make sure their assets are protected.

These rules are all born from the idea of margin trading. When a trader takes a short position, they must take out a loan from their broker. This loan helps the trader by reducing the amount of cash they need to spend on the trade; however, it also creates certain obligations. Below is a summary of the most important terms in margin trading, and an example to explain each term.

- Initial Margin Requirement: the percentage of the cost of a trade that the trader will have to pay from his own cash. This is traditionally 50%.

- Margin Maintenance Requirement: the amount of cash a trader needs to have in their account while they hold their position. This typically falls around 25% of the current value of the securities in the margin account.

- Total Margin Requirement: the required margin to hold a trader’s position. This is traditionally 100% of the market value of the short sale and the margin maintenance requirement.

- Margin Call: a warning issued when the trader’s total margin requirement exceeds the value it had when the short was first initiated.

- Liquidation: a broker may liquidate the trader’s position if total margin requirements are exceeded. By reclaiming its stock, the broker leaves the trader with the cost of the loss of the trade.

An example

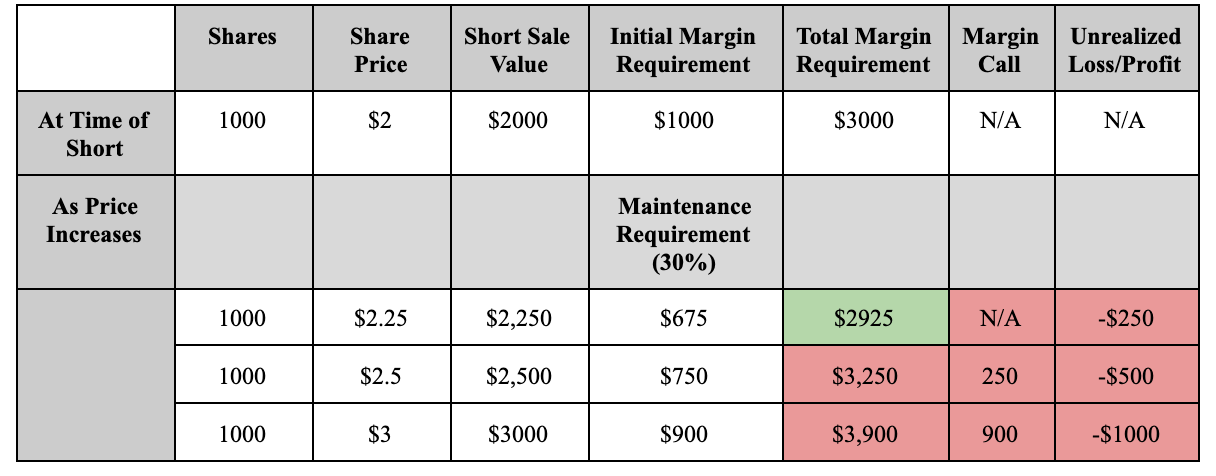

Suppose you’re shorting 1000 shares of “XXX” at $2 for a total cost of $2000. With an initial margin requirement of 50%, you will only need to pay 50% of the total cost, while the remaining 50% will be given to you by your broker as a loan. Thus, you pay $1000, receive a $1000 loan, and you initiate your short position at $2 a share. Suppose your margin maintenance requirement is set at 30%. Let’s see what happens when the stock’s price changes.

Consider the following observations

- Short Sale Value: this column shows how the share sale value increases as the share price increases. During a short, the trader wants this value to decrease. This value is calculated by multiplying the amount of shares with the share price.

- Maintenance Requirement: this column shows that the maintenance requirement varies with the price of the stock. It’s calculated by multiplying the maintenance requirement percentage by the short sale value

- Total Margin Requirement: this column shows the sum of the short sale value and the maintenance requirement at different prices. It’s extremely important that the total margin requirement remains below what it was at the time of short, or a margin call is made.

- Margin Call: this column shows the amount a trader needs to deposit into his account or risk losing their short position. It’s calculated by subtracting the total margin requirement at time of short by the total margin requirement at current price.

- Unrealized Loss/Profit: this column shows how much money is made or lost depending on the price of the stock being held. It reiterates the idea that short sellers make money when the price decreases and lose money when the price increases. It’s calculated by subtracting the short sale value at time of short and the short sale value at time of the current price.

This table tells you the story of collateral. It shows you the tightrope that you tread on as a short seller. Notice, for example, how if the stock price rises above $2.25, a margin call will be issued, and the trader will have to deposit the margin call amount or have his position liquidated. A similar story is told as the price rises to $2.5 and to $3, as both the margin call value and the unrealized losses continue to rise.

The trader risks not only liquidation but also other fees like the ones below.

- Hard-to-borrow fees may be accrued by the trader if the stock they’re looking to short is difficult to borrow. This fee is calculated in the same way as margin interest with the hard-to-borrow rate instead of the margin interest rate.

- Dividend payments belonging to the owners of the stock fall under the cost of the borrower if they are holding it while a dividend payment is declared.

The short seller has margin calls, margin interest, hard-to-borrow fees, and dividend payments to worry about. You might be wondering why a trader would go short given the many roadblocks to short selling. Let’s look at another table to see why.

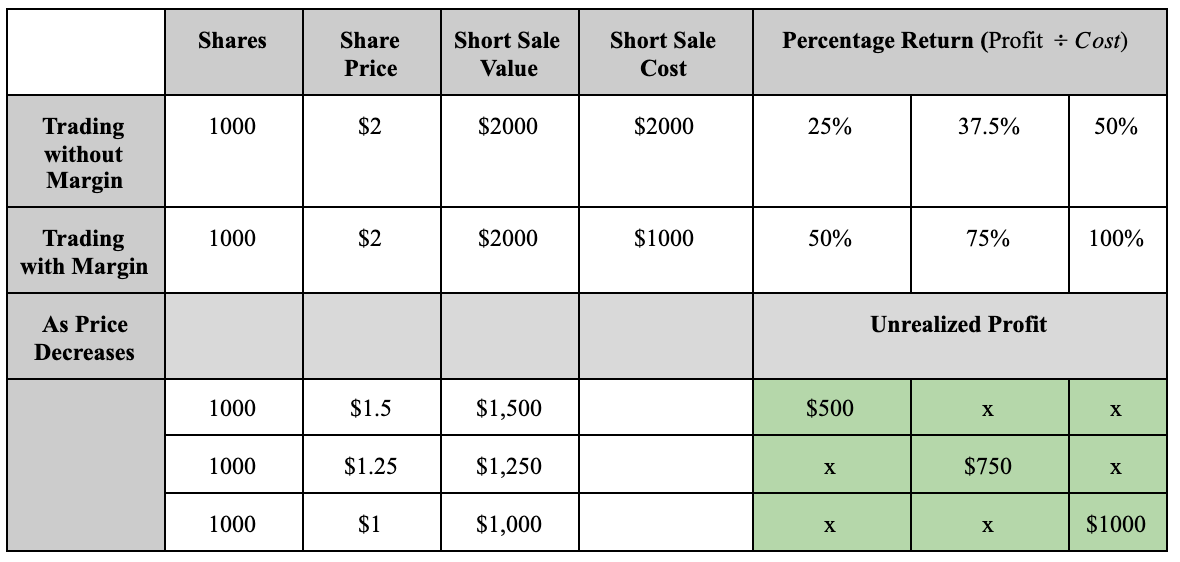

This table shows the difference in percentage returns when trading with and without margin. Consider the price decrease to $1.5 as an example. When trading without margin, a $500 win would mean only a 25% return since you would incur the full cost of the short sale value (500/2000 x 100). In contrast, when trading with margin, a $500 win would mean a 50% return since you would only incur half the cost of the short sale value (500/1000 x 100). The same pattern is seen with a price decrease to $1.25 and a price decrease to $1, where percentage returns are double with margin than without.

One can see the allure to short selling and margin trading here. The prospect of at least doubling one’s winnings seems incentive enough for a lot of traders to negate the stringent rules imposed by their brokers and the fees associated with short selling.

Hedging to decrease risk

In the above examples, the trader initiated a short with a sole purpose: capture profit. A more cautious method of shorting involves using shorts to protect an investment in case it goes the wrong way. This is called hedging, and the idea is straightforward.

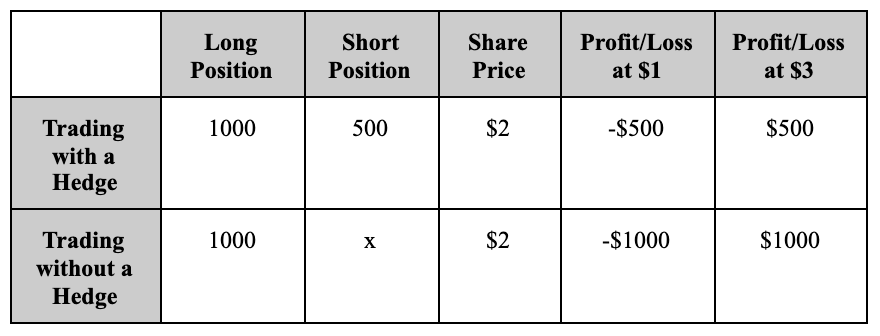

When you initiate a trade on an asset expecting its price to increase, you also place a short position. This way, if the asset’s movement does not meet expectations, the loss is minimized by the profits gained from the short. There’s a catch to this reduced risk: if the price of the stock does increase, the profit gained will be minimized by the losses from the short position. The table below describes the hedging relationship in numerical terms.

As the table demonstrates, the trader with a hedge reduces both his potential winnings and his potential losses by engaging in a hedge. In poor market conditions, this is a wise risk management strategy for long setups, and a strategic way to use short selling for loss aversion rather than profit capture.

Short selling: additional concerns

If you think you’ve heard most of the concerns around short selling, you’re wrong. There are still several factors that scare the average trader away from shorts.

- The Overall Trend of the Market: A long term short position on a stock or a market index is considered a risky endeavour by most traders because one would be trading against the overall trend of the market. The S&P500, for example, has experienced steady growth from as far back as 2009, rising about fourfold since that time. Other indices show similar growth patterns. One must have a very strong reason to bet against these numbers if they were to take a long-term short position.

- Unlimited Losses: When you go long, there’s a finite risk in your trade. If it fails in the most horrible way, and the stock you bought goes to $0, you only risk the difference between the price you purchased the stock at and 0. With short selling, however, there’s no limit to how high a share of stock can go; thus, a short seller’s theoretical loss is infinite. This risk can be mitigated through a stop-loss plan, but the theory still rings true.

- Short Squeezes: When a great number of shorts are taken on a stock, and these shorts reach their stop losses, they will be forced to cover. The intense buying from shorts covering their positions and other long-biased traders purchasing the stock can create a huge imbalance in the buyer-seller dynamic, which would cause the stock’s price to skyrocket. As a short seller, if you’re caught in this squeeze, the damage can be colossal. GameStop’s value rose from $20 to $350 in just a couple of days as a result of a short squeeze in early 2021.

Why do you short?

So there you have it. Shorting is scary. It’s got fees. It’s got liquidity issues. It’s got margin calls. It’s got rules that are difficult to understand let alone keep track of. Sure, the prospect of making double on your percentage returns seems cool, but why on earth would you put yourself through all that trouble if you can just focus on going long?

The simple answer is aptitude.

If you’re good enough at determining an asset’s price is about to fall, the risks and costs of short selling become negligible. There’s a multitude of very well known short-sellers who have made their fortunes through “going against the tide.”

For the younger generation, perhaps the best known trader is Michael Burry, whose story was told in the Hollywood movie The Big Short. But the world is filled with short-biased traders. Jim Chanos, John Paulson, and Steve Watson have all made the majority of their fortunes through bearish endeavours like short selling.

Being a successful short-seller, however, does not mean you only ever sell stocks short. The long-biased trader and short-biased trader are not mutually exclusive. For example, there are traders who are great at deciphering when a trend has shifted, and they engage in both buying and shorting, depending on where the trend is taking them.

In the end, a trader’s largest cost, fee, or risk is never monetary, but in a quality that’s lacking. Ineptitude and indiscipline are amongst the chief risk factors of any trading activity, and they take precedence over all other risks.

What are some things to look for when shorting?

Traders use different principles to determine whether something is a good short or not depending on their style, positions, the duration of their shorts, and other factors. Here are some of the most common “confirmations” of short selling.

- Technical Indicators: staying true to the idea of reacting rather than anticipating, many short sellers like to wait until they’ve seen several technical indicators “confirm” that the stock is currently at a price level that’s about to drop significantly before they take a short. For many, resistance, support, and moving averages play a key role in determining when a short sale has been “confirmed” and has a higher likelihood of succeeding.

- Fundamental Reports & Catalysts: Playing a key role for investors like Warren Buffet, fundamental catalysts and reports have long been used to determine whether a stock is worth shorting or not. A pattern of deteriorating financials, for example. might help a short seller feel more certain of their short position. A negative catalyst like a company being sued for fraud would be another positive for a trader looking to short that company’s stock.

- Market Conditions: When the market is going through a “bearish” phase, and many stocks are trending downwards, the short seller has more confidence that their short selling will work in their favor. Market conditions are like the ocean’s current - you will generally get further if you’re moving with it rather than against it.

Stock Alarm alerts that could help your short selling

Stock Alarm has a variety of alerts that can help a trader with their short selling. Trailing Buy Stop Alerts, for example, notify a trader once their short position is about to hit their stop loss. This works on a percentage and a per dollar basis. Upper Price Limit alerts, on the other hand, may help a trader take a short at a well-respected resistance level, allowing them to enter at an ideal price before the stock’s price falls. Other alerts like the 1-Day Price Change, RSI Overbought, and MACD can be used in the context of short selling to help you maintain that competitive edge.

To short or not to short

You may look back at our earlier analogy and deem it too simplistic. As we’ve discovered, there are several more risk factors and threats to the short seller than there were to you when you were trying to pawn John’s chair off for a profit.

But what we have also seen is how much margin trading can help an account grow, and how many investors have made short-selling a profitable and sustainable strategy for wealth growth. We’ve even considered hedging, and how a trader may use short selling for risk aversion rather than profit capture.

The success side of short selling serves as a testament to our IKEA chair short-selling endeavors. It tells us it could be that easy. But if, and only if, you’re good enough.

Disclaimer

DO NOT BASE ANY INVESTMENT DECISION UPON ANY MATERIALS FOUND ON THIS WEBSITE. We are not registered as a securities broker-dealer or an investment adviser either with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC”) or with any state securities regulatory authority. We are neither licensed nor qualified to provide investment advice. We are just a group of students who diligently follow industry trends and current events, then share our own advice, which reflects our personal position in the market.